What is Marburg virus? 5 things to know about the Ebola-like virus

In February, the World Health Organization confirmed the first-ever Marburg virus disease outbreak in Equatorial Guinea. As of the latest WHO update from April 17, officials report 15 confirmed and 23 probable cases, with 34 deaths among them.

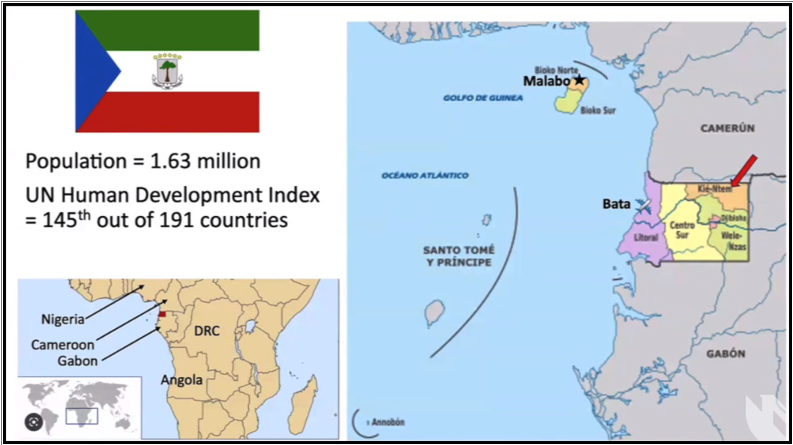

The outbreak began in the rural area of the Kié-Ntem province, which borders Cameroon and Gabon, but cases have subsequently appeared across much of the country. Bata Province now has the highest number of confirmed cases. It is 80 miles from the original outbreak zone and has a large urban center with the only international airport in the continental portion of Equatorial Guinea.

“Equatorial Guinea doesn’t have the best public health infrastructure. While we haven’t seen an explosion of cases, international experts are not clear about the effectiveness of surveillance,” says James Lawler, MD, Nebraska Medicine infectious diseases expert. “We will see in time.”

Equatorial Guinea is a country on the West Coast of central Africa with a land area roughly equivalent to the state of Maryland. It has an estimated population of 1.6 million, mainly split between the larger continental portion and the island of Bioko (100 miles to the northeast), where the capital city, Malabo, is located. Travel between Equatorial Guinea and the U.S. is rare, with most air travelers transiting through Spain.

Marburg virus has been most frequently found in Uganda and Kenya around Lake Victoria. The fatality rate in previous outbreaks has averaged close to 80%. The largest Marburg virus outbreak occurred in 2004 and 2005 in Angola, resulting in 374 cases. The disease is transmissible from person to person. In the past two years, there have been detections in Ghana (2022) and Guinea (2021) in West Africa. In late March, a new outbreak of Marburg virus disease was reported in the northwest corner of Tanzania, on the shores of Lake Victoria. There have been nine reported cases to date. It is unclear whether this outbreak is related to the one in Equatorial Guinea, but the geographic separation (1,500 miles) makes that unlikely.

What is Marburg virus?

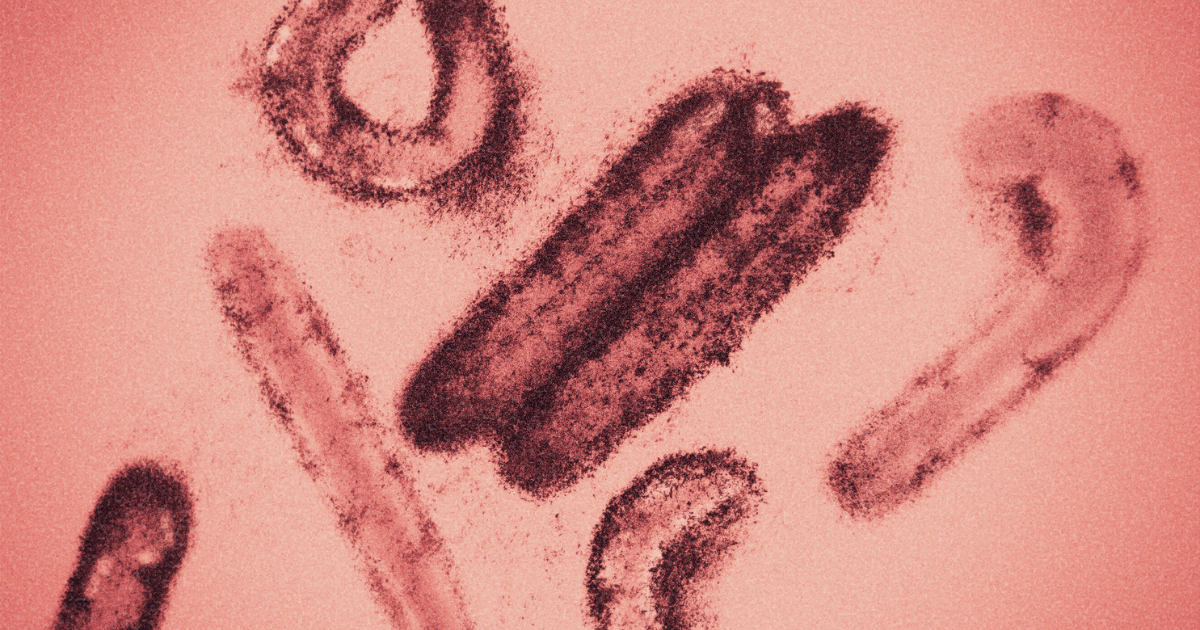

The Marburg virus is a filovirus (a cousin of Ebola viruses), causing a hemorrhagic fever similar to that of the Ebola virus. Like Ebola, it can be transmitted from person to person, typically through close contact with people who are very sick. Many people infected in Equatorial Guinea appear to have had contact with human remains at funeral ceremonies.

How is the Marburg virus transmitted and spread?

Fruit bats are considered natural hosts for the Marburg virus, but the virus can also infect primates, pigs and other animals. Human outbreaks likely start when a person has direct or indirect contact with an infected animal.

Marburg can spread through:

- Broken skin or mucous membranes

- Blood, secretions, organs or other bodily fluids of infected people

- Bedding, clothing or surfaces contaminated with bodily fluids of infected people

- Direct contact with an infected, deceased body

Where did Marburg virus come from?

Marburg virus disease was initially detected in lab workers working with African green monkeys imported from Uganda in 1967. Concurrent outbreaks occurred in Marburg and Frankfurt in Germany and Belgrade, Serbia. The virus got its name from Marburg, Germany.

What are symptoms of Marburg virus disease?

Marburg virus disease begins abruptly after an incubation period between two to 21 days. Severe disease can appear between five and seven days from the start of symptoms.

Similar to Ebola, symptoms include:

- High fever

- Severe headaches

- Extreme fatigue

Typically occurring on or by day three, symptoms become severe and include:

- Watery diarrhea, abdominal pain and cramping

- Nausea and vomiting

- After this phase, bleeding begins to occur

Marburg virus prevention

There is no vaccine or antiviral treatment for the Marburg virus, but development with clinical trial considerations is underway.

High-quality surveillance and case detection, finding and isolating sick and infected people, tracing their contacts, and quarantining contacts help prevent transmission.