Clinical trial shows promising results in certain types of non-Hodgkin lymphomas

University of Nebraska Medical Center researchers are studying an experimental treatment for patients with specific subtypes of B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphomas. Potential candidates include patients who have undergone prior standard therapies that are no longer working or who have had cancer continue to return.

When Nebraska Medicine oncologist Christopher D’Angelo, MD, referred James Potts as a potential candidate, his large B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma repeatedly returned despite trying multiple treatment types. “I am five weeks into the trial and feel great so far,” says Potts. “Everyone was so excited seeing my latest scans.”

Treatment is given initially as a weekly stand-alone, injection just below the skin, followed by labs and monitoring after each visit, then transitions to every other week. Eventually, patients transition to one injection per month, followed by labs and monitoring.

How does it work?

The epcoritamab bispecific antibody has two prongs: one attaches to the cancer cells and the other to T lymphocytes (T-cells). T-cells help our bodies fight infection and cancer. In a person with cancer, they become exhausted and don’t function properly. This therapy attempts to bring the patient’s T-cells closer to the cancer cells so the immune system recognizes it as a foreign substance and works to kill the cancer cells.

Since this is a clinical trial, the outcomes and side effects are not yet known with this experimental treatment. Among the goals are to learn more about this drug’s side effects and its effectiveness. Some side effects of the treatment may include skin redness or itching, fever, low blood pressure or an allergic reaction. Rarely, neurotoxicity can occur, causing confusion, headaches, seizures or breathing difficulty.

Similar, yet different than CAR T-cell therapy

While both treatments attempt to help the patient’s immune system fight cancer, there are differences. CAR T-cell therapy takes a patient’s cells out of the blood, genetically modifies them and gives them back to the patient after three days of chemotherapy. Returning a patient’s CAR-T cells to their blood may help their immune cells find and fight cancer. The epcoritamab bispecific antibody treatment is a readily available (off the shelf), stand-alone injection with no other simultaneous therapies.

“So far, the results appear promising,” says Julie Vose, MD, oncologist and principal trial investigator. “The final outcome of the trial will determine if the medication will be available for other similar patients.”

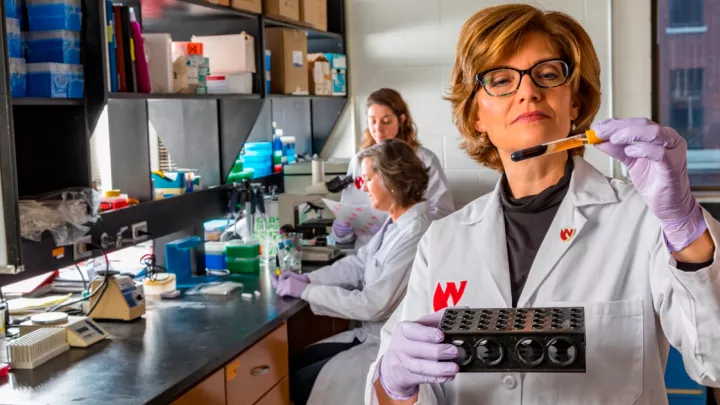

The Nebraska Medicine lymphoma team works together to help patients achieve the best possible outcome, and clinical trials offer the opportunity to provide new, innovative ways to fight cancer in the future.

“The whole team has been super,” says Potts. “Susan Blumel, my case manager, and Dr. D’Angelo have been wonderful. Everyone has been so professional and family orientated. I’m so thankful for the trial team working with my oncology team. Their sense of humor has helped us get through all of this!”

A referring oncologist can help a potential candidate start the evaluation and screening process with Nebraska Medicine to determine eligibility.